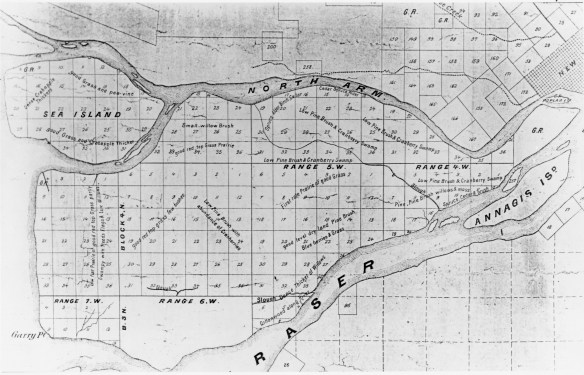

The City of Richmond is built on islands located on the flood plain of the Fraser River, surrounded by the river and exposed to the Strait of Georgia on the west. With an average elevation of just one metre above the present mean sea level, Richmond faces flooding from extreme storm surges, intense rainfall, high tides and seasonal rises in river flows and levels. It was not until the arrival of non-Indigenous settlers in the Lower Mainland that textual records of floods and the damage they caused to dykes, crops, livestock and structures were made, most often in the newspapers of the day. Early landowners in Richmond began the process of dyking the land, usually their own properties, and building flood boxes to allow drainage at low tide and blocking the ingress of water at high tide. Soon, dyking districts were formed which provided funds for dyking and drainage projects through taxation and by the mid 1930s these were amalgamated under the control of the Richmond Municipality. The improvements made by Richmond over the years, ditches, canals, electric pump stations, box culverts and dyke upgrades, have greatly lessened the impact of floods on the city. This post describes some of the floods that occurred through Richmond’s history and some of the steps taken to reduce their consequences.

November 1871 – An intense storm blowing up the river combined with a high tide and storm surge caused dykes to be washed away in Ladner and flooding to occur. While Richmond, which was not incorporated until 1879, was not mentioned in reports, the storm did cause significant damage to the Sand Heads Light Ship, dismasting it and tearing up parts of its deck. It was towed to New Westminster for repairs.

May to June 1894 – The “Great Flood of 1894” caused extensive flooding and damage all through the Fraser Valley. An extreme spring runoff brought on by a cool summer of 1893 which failed to melt snow in the mountains, a record snowfall through the winter of 1893-94 and rain and a heat wave at the end of May raised river levels to the highest ever recorded, 25.75 feet at the Mission Bridge. Dykes were destroyed, bridges and wharves washed away and farms were inundated destroying crops and drowning cattle and causing substantial loss of human life. In Richmond by June 1st, the flood had scoured out the fill around the pilings on the newly completed North Arm (Fraser Street) Bridge, causing about 200 feet of it to be carried away a few days later. Lulu Island was reported to be seriously flooded due to breaks in the dyke at Scott’s Mill at the Queensborough end of the Island and then over the main dykes at high tide. Damage in Richmond Municipality was estimated to be $2000 to the North Arm Bridge and a further $7000 in crop loss due to the flooding.

January 1895 – Six months after the 1894 flood, Lulu Island was again hit by flooding, this time by a combination of high river flows and extreme high tides with a strong west wind. Dykes on Lulu Island were washed away in many places, flooding large areas of farmland. Root crops stored in pits were destroyed along with large quantities of potatoes. Houses and barns were flooded and bridges over ditches and canals were washed away. Sea Island was reported to be under as much as three and a half feet of water. In Steveston water flooded over the floors of canneries and some residents had to leave their houses. Steveston’s plank roads floated and were swept away by the water.

1900 – The first of Richmond dyking districts was formed when landowners petitioned the Provincial Government to allow taxation for the construction of dykes and drainage systems under the authority of the Drainage, Dyking and Development Act. The New Lulu Island Slough Dyking District was responsible for the land encompassing the slough complex from Francis Road south to the river. Before this time landowners dyked their own property with other areas being handled by the Township. Commissioners were elected to administer the district and an engineer was hired to draw up technical plans and assessments of the land.

December 26-27 1901 – Richmond was hammered by a severe gale directed squarely at the mouth of the Fraser combined with very high tides. This was the most extensive and damaging flood in Richmond since 1894. Several canneries were heavily damaged and one, the Labrador Cannery at Terra Nova, was completely destroyed. Miles of dykes were lost along the North and Middle Arms of the river, fishing boats were swept as far as half a mile into farmer’s fields and smashed up. The Japanese boarding house at Terra Nova collapsed with people trapped inside who were rescued by neighborhood residents. Another boarding house with nine men inside was swept into the river. They managed to get on to the roof of the building where they were rescued by men who braved the storm in two boats. Sea Island and the greater part of Lulu Island were reported to be flooded by two to four feet of water. Steveston was under water and the floors in the Gulf of Georgia cannery were completely covered. Outbuildings at the Colonial Cannery were washed away and the plank roads in Steveston and around Lulu Island floated away.

1905 – The second of the dyking districts was formed. The Lulu Island West Dyking District was formed with responsibility for the area west of No. 3 Road.

November 1913 – The highest tides in ten years combined with a storm surge and high winds caused dykes to give way in many places flooding hundreds of acres of farmland. On Lulu Island, the Bridgeport area was inundated. Water covered roads and fields up to two feet deep, while Bridgeport School was surrounded with about three feet of water. Sea Island was similarly affected with about 500 acres of land flooded after the North Arm dyke was breached at the Cooney property on No.13 (Miller) Road. Damage was fairly light at the north-east corner of Sea Island, although the store and meat market sustained significant damage.

January 1914 – Through January 1914 heavy rains and high tides rendered the municipal drainage systems useless causing high water all along No.20 (Cambie) Road from Bridgeport to No.5 Road. The Bridgeport, Cambie and Alexandra areas were flooded with up to two feet of water. Later in the month, the same conditions, worsened by a gale force wind, washed away 150 feet of the dyke on Sea Island, completely flooding the island. Mitchell island, along with smaller islands in the river were also completely flooded. At a ratepayer’s meeting after the flood, keynote speaker John Tilton stated that “…well dyked and well drained, this island would be a beauty spot of Canada. As it is, it is no better than a duck pond.”

January 1921 – Once again the double hit of heavy rain and high tides caused flooding in Richmond. The flood box on Twigg Island was washed away, resulting in the island being completely inundated every time the tide came in. On Mitchell Island a poorly reconstructed dyke, built after the construction of Union Cedar Mills, allowed tide water to surge over and flood the island. On Lulu Island unfinished dykes on the North Arm and on the South Arm at the London property allowed the water to wash over. Large parts of the Alexandra and Garden City areas were flooded. A public meeting held at Richmond Townhall saw citizens, who had already willingly taxed themselves for dyking and drainage to an amount equal to half the general taxes of the municipality, advocating for the installation of powerful electric pumps to drain the island.

January 1933 – The New Lulu Island Slough Dyking District installed the first electric pump in the dyking and drainage system on the South Arm between No. 3 and No. 4 Roads. The 60 horsepower pump would operate automatically only during the highest tides when the flood boxes become ineffective. The pump was expected to remove 16000 gallons per minute and would drain about 4300 acres of land.

January 1935 – Heavy snowfall followed by higher than normal temperatures and heavy rain caused flooding in the Fraser River Valley and drainage problems in Richmond. Lulu Island was reported to be a series of small lakes and Lansdowne and Brighouse Racetracks were completely flooded.

1936 – The Township of Richmond amalgamated its own works with the other two dyking districts, assuming control of all dyking and drainage activities within its boundaries. The work done on the dyking and drainage system was beginning to have a positive effect on flooding problems in Richmond. While some flooding due to high rainfall was still problematic at times, residents did not seem too concerned about the occasional time when one had to wear gumboots to go into their yards. The Richmond Review boasted in the October 6, 1936 edition, “Richmond the Dryest Place in the Valley.” “Richmond should let the world know that it is about the safest place in time of flood from Winnipeg west. Richmond is so near the sea that excess water can readily escape if given half a chance.” The attention given to improving and upgrading dyking and drainage systems was to continue up to the present day.

February 1945 – “The Great Storm of February 7, 1945” was claimed to have caused the worst flood in ten years. Vancouver newspaper reports said that Burkeville was a chain of lakes with about 25 houses surrounded by water, stranding the residents inside. Acres of Lulu Island were under water. However, the Richmond Review reported, “Flood of Short Duration Here.” The rain which caused ditches to fill and property to flood on Wednesday had all run off by Friday.

1948 – In January high tides and storm surge burst through the dykes on Twigg Island. On Lulu Island a few houses were subject to flooding. Then, in May and June the Fraser Valley was hit by the worst flood since 1894. The 1948 flood was one of the most destructive in BC history, causing widespread damage throughout the Fraser Valley. Richmond, however, got off relatively easily because of the the tremendous organization and mobilization of every available resource led by Reeve (Mayor) R.M. Grauer. With help from the military, volunteer labour from Richmond and other cities in the Lower Mainland and some paid labour, the dykes were monitored 24 hours a day, thousands of sandbags were filled, brush along the dykes was cleared and weak spots in the dykes were shored up. Organizing and supervising the workers on the dykes were Ken Fraser, who took care of Steveston to No.2 Road, Archie Blair, the area between No.2 Road and No. 4 Road, Leslie Gilmore, No. 4 to No.6 Roads, Matthew McNair, No.6 to No.7 Roads, Andy Gilmore, No.7 to No.9 Roads, E. Carncross, No.9 Road to Hamilton, Bob Ransford, Hamilton to the eastern boundary, and Doug and John Savage, the northern boundary to No.8 Road. G. Crosby monitored the Middle Arm dyke on Lulu Island and on Sea Island the Grauers watched the North Arm dyke to Cora Brown, Doug Gilmore, the rest of the North Arm Dyke, Cline Hoggard, the Middle Arm to the Airport and the rest was watched by the Airport Authorities.

The logistics involved in the “Battle of the Dykes” were akin to a military operation. Hundreds of workers were mobilized and directed to their stations. Canteens were set up at the various command posts, supplied with coffee, sandwiches, soup, cigarettes, donuts, cases of pop and cookies provided by the Municipality, the Red Cross or donated by Lower Mainland businesses and churches. Drivers were busy delivering supplies to the dykes and the canteens. Businesses and private citizens donated the use of cars, trucks and tractors to the effort. The military provided manpower, vehicles, boats and powerful tugs, able to pull barges of rock and earth against the strong current in the river. To help with communications the BC Forest Service provided two mobile radio units, The BC Telephone Company installed temporary telephones at command posts and BC Electric provided power where necessary. All movement of deep sea vessels was suspended on the river. Towing companies were instructed to use only more powerful tugs, speed limits were imposed to prevent damage to dykes and the size of tows was restricted to single barges and booms with an assisting tug. Bridges were closed to traffic from two hours before until two hours after high tide slack.

To make sure that workers remained focused on the job at hand, the liquor licenses at the Steveston Hotel, the Steveston and Sea Island ANAFs and the Royal Canadian Legion were temporarily suspended. In the event that the worst happened, a train was stationed at New Westminster to assist in evacuating people from Richmond.

The constant monitoring, shoring up of low spots and reinforcing dykes that began to weep paid off in a minimum of damage in the Municipality. There was only one significant problem reported when a “geyser” erupted on the dyke at the Rice Mill resulting in a breach. About 100 yards of the dyke had collapsed into the river at high tide. Fortunately, as the tide receded the flooding stopped and the gap was filled using the Municipal dragline. Repair work was completed before the tide came back in and flooding didn’t penetrate past the CN Rail line.

November/December 1951 – In late November a near hurricane storm system and high tidal surge hit the Lower Mainland. At Richmond, River Road near the Sea Island bridge was under about 6 inches of water. Workers from the Lulu Island Canning Company were set to work packing the dykes with sandbags. In nearby low lying areas houses were surrounded by water up to 10 inches deep. The high tides and strong winds breached a low dyke at the end of No.2 Road in Steveston but the water was held back by a higher inside dyke. The ferry to Ladner was put out of service when a pontoon at the Richmond ferry terminal sank.

January 1953 – Dirt fill around the new $15000 flood box at Finn Slough washed away resulting in the destruction of the flood box. About 50 yards of the dyke near the foot of No.4 Road washed out “as if cut by a knife.” The location of the break was such that trucks could not be brought in so Councillor Archie Blair used his farm tractor to bring in sandbags and to push mud into the breach and a scow delivered a load of soil. Flooding caused significant damage to the Gilmore farm buildings and the family home. It was discovered that wing dams and modifications made by the Federal Government to the south shore of the river in an attempt to increase the water velocity and make the river “self-dredging,” redirected the flow, causing it to scour the area between Woodward’s Landing and Steveston and undermine the dyke. High seasonal tides then ended up breaching the dyke. The dyke was subsequently repaired and armoured with rock.

November 1954 – Very heavy rainfall overwhelmed the drainage system causing an accumulation of water in Richmond that filled ditches and backed up onto the surface of the land. The No.3 Road pump had lost a top main bearing making the situation worse. The most affected area was in the Grauer subdivision and the rest of the area drained by the No.4 Road canal. Crown Zellerbach helped out by placing nine large pumps at Finn Slough which assisted the municipality’s pumps by drawing an additional 22,000 gallons a minute.

November 1955 – Heavy rainfalls caused flooding around the Lower Mainland but, according to reports in the Vancouver Sun, flooding in Richmond was “much less than expected.” While some ditches overflowed onto roads, fields and lawns, the municipality’s canal drainage system speeded up the runoff significantly.

December 1957, January 1958 – High tides, wind and heavy rain caused water to go over the dykes on Mitchell Island. About 100 homes in Richmond were surrounded by water due to blocked drains in the drainage system.

December 25-26 1972 – Water from rain melting snow caused flooding around Richmond, and damage at the municipal offices.

February 1976 – An exceptionally high tide caused flooding one foot deep around about fifty homes in the Cambie and River Road area when a temporary rock dam was breached where a new pumping station was being installed on the Middle Arm.

December 1979 – Once again, extremely heavy rainfall caused drainage problems around Richmond. The flooding caused sanitary sewers to back up at London Junior Secondary School, flooding the gym and closing the school. Wet cables caused the loss of telephone service to about 1000 customers.

To the present- The improvements made to Richmond’s dyking and drainage system have been continuous since the first hand built dykes in the 1800s. Today, around 49 km of dykes hold back water from the sea and the river. 598 km of drainage piping, 61 km of culverts and 151 km of open watercourses move water out of the city. Thirty-nine pump stations, capable of removing 5.3 million litres of water per minute, are ready to discharge rainwater to the river and ocean. Sensors provide real-time information about river levels, rainfall and the drainage of storm water and analysis of weather patterns, snowpack and predicted runoff warn of potential risks to the city. Regular inspection and maintenance of the whole dyking and drainage system takes place with increased patrols during higher risk periods. Richmond’s dyking and drainage system is designed to withstand a one in 500 year flooding event, something that has a 0.2% chance of occurring in any given year. A case in point is the 2021 atmospheric river event, which broke rainfall records around the Pacific Northwest and caused extensive damage in many places, was handled well by Richmond’s system although localized drainage problems did occur.

To the future- To prepare for climate change induced sea level rise and increased rainfall the City’s Engineering and Public Works Department has developed a flood protection strategy to prepare for emergencies. To ensure Richmond and its residents remain safe, the City has one of the most comprehensive flood protection systems in BC. To learn about it, visit the City of Richmond’s website at https://www.richmond.ca/services/water-sewer-flood/dikes.htm

You must be logged in to post a comment.