Clarence Sihoe 5 November 2025

Introduction

In late 2017, after almost fifteen years of research, I completed a book that explored the history of my mother’s family in Canada. Driven by curiosity and passion in equal measure, the work enabled all in our extended family to better understand our roots in this land and strengthen the bonds that keep us closely connected. It was satisfying to finally get the project done.

My maternal grandfather, YEE Clun, left his home village in Hoi-Ping (Kaiping) county, Kwangtung (Guangdong) province, China, and arrived in Victoria in September 1902. He paid the head tax of $100 to enter the country. Working first as a labourer, he eventually earned status as a merchant, owning and operating a number of restaurants and cafes and an import-export business in small towns and cities across Saskatchewan. This enabled him to bring my grandmother, ARNG Woon Goke, to Regina in late 1919, exempt from the head tax. There they raised a family of six children until their return to China in 1932. They reunited in Regina in 1941 and finally settled in Vancouver in the fall of 1947.

My journey to uncover these details led me down a countless number of trails: some productive, others complete dead ends. I arranged many conversations with my mother, aunts and uncle; organized a small part of our collection of family photographs; visited libraries and archives in B.C. and Saskatchewan; read dozens of articles and newspaper stories on the internet; and requested and received documents from various provincial and federal government agencies. Of great value early on were the materials held by the Vancouver Public Library Chinese Canadian Genealogy section. The records held by Library Archives Canada were also very useful, particularly the Immigrants from China database, and they continue to be an important resource for family historians and professional genealogists alike.

The year 2023 was recognized as an important date by many members of the Chinese Canadian community, for it marked the one hundredth anniversary of the passing of the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923. This federal legislation, commonly known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, more or less ended immigration of the Chinese people to Canada. There were few exceptions to this legal form of discrimination. For a quarter century until its repeal in 1947, this unjust and cruel law kept thousands of men living and working in Canada apart from their wives and children who remained in China. Some of these so called “bachelors” never reunited with their families, and they died alone in a country that may have welcomed them at first but then denied them a chance to fully participate or contribute towards the growth of this society. The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, an exhibit curated by Catherine Clement, explored this dark period in our history and was featured at the Chinese Canadian Museum, located in Vancouver’s Chinatown, for eighteen months that began on 1 July 2023. A digital archive of the documents displayed at the exhibition is held at UBC Library, Rare Books and Special Collections. https://rbscarchives.library.ubc.ca/paper-trail-collection

These historical facts have led me to think more about Richmond. I worked within its local government for almost three decades and I’ve resided here since 1991. My aunt, uncle, and cousins lived near the corner of No. 1 Road and Francis Road in the 1960s, but recently I began to wonder about the Chinese people who settled here over a century ago. Who was present when the Exclusion Act came into force in Richmond? The stories of the Chinese fish cannery workers and farm labourers have been documented, mostly single men who worked these seasonal jobs, and then perhaps retreated to Vancouver’s Chinatown during the wintertime. But what of the families who may have lived here? How many men and women were fortunate enough to stay together, earn a living, and raise a family on Lulu and Sea Islands?

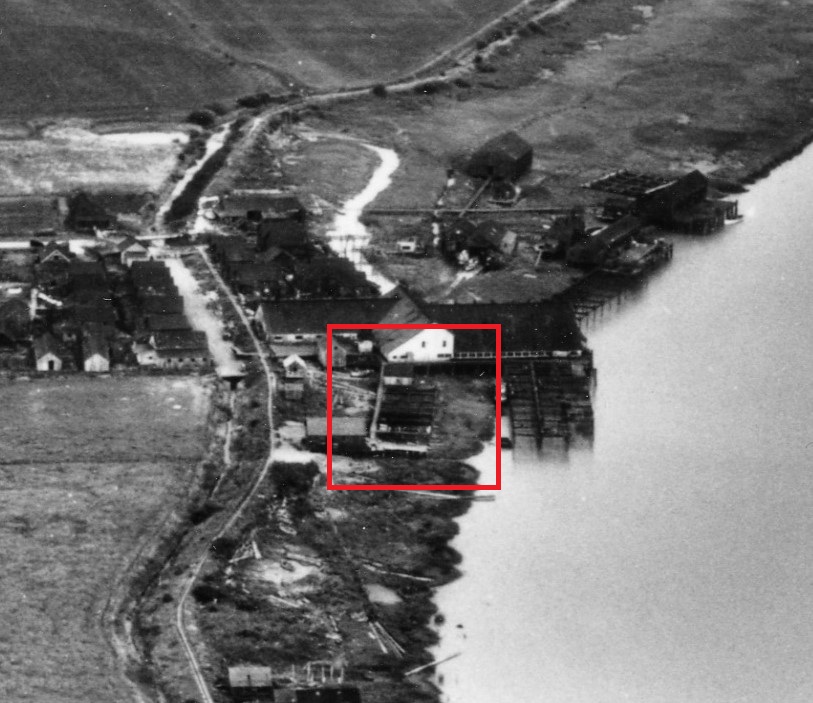

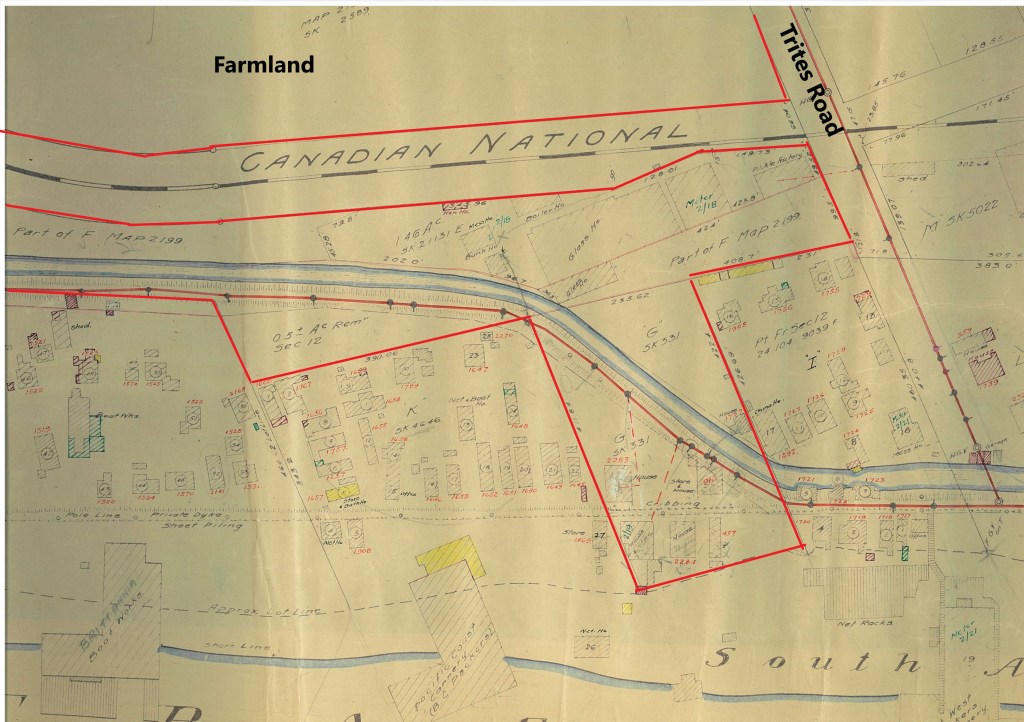

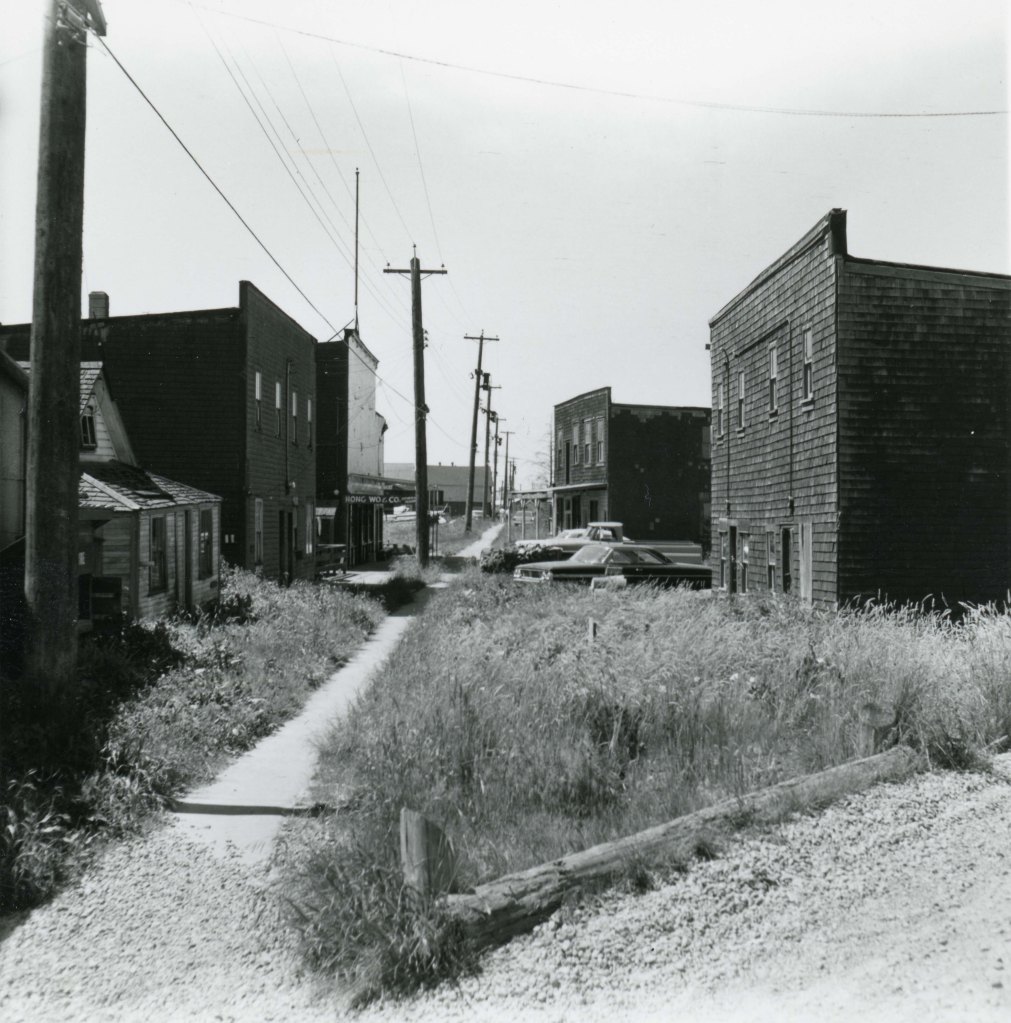

My research these days focuses on discovering the identities of these people, and I begin with LAM Ching Ling, proprietor of the Hong Wo Store in Steveston. His career as a general merchant, farmer, and labour contractor is well known, and has been highlighted in an informative and interesting post from May 2023, researched and written by John Campbell, Social Media Coordinator with the Friends of the Richmond Archives. https://richmondarchives.ca/2023/05/11/peace-together-ling-lam-and-the-hong-wo-store/

To start my search, I visited the City of Richmond Archives last fall. Knowledgeable staff there pointed me towards an impressive number of municipal and community records available for consultation. These included Council minutes, voters’ lists, and directories. Most important was A Thematic Guide to the Early Records of Chinese Canadians in Richmond, prepared for the Archives by Claudia Chan in August 2011. It is an excellent summary of all the records pertaining to early Chinese Canadians held by the Archives at that time. Reading this led me to the biography files of some of the early Chinese pioneers of Richmond, LAM Ching Ling among them.

His connection to the fishing and farming industries was well documented, but more personal details about his life with family and community were scant. Using the array of genealogical resources now available, my goal is to begin adding extra layers of details to his biography, so that we may better come to know this important figure in the story of our City. I see this as the first in a series of similar stories about the other Chinese Canadian pioneer families of Richmond.

LAM4 Zoeng1 Ling6 (in Jyutping Cantonese romanization); LIN Zhang Ling (in Pinyin Mandarin romanization); LAM Ching Ling.

LAM Ching Ling was born on 1 August 1873 in Sun Wui county, Kwangtung (Guangdong) province, China. Sun Wui is also known as SunWoy and as XinHui in Pinyin. The village where he is from has been written as Goo Chung, Goo Dung and Kwo Jung in various Canadian government documents.

Ling LAM (City of Richmond Archives Accession 2013 52.)

He arrived in Vancouver, B.C. in March 1890 aboard the vessel S.S. Abyssinia, and registered with the authorities on 7 March 1890. Prior to departure from Hong Kong, he had paid the $50 head tax to enter Canada.

His name was recorded in the General Register of Chinese Immigration as JUNG Ah Tuen and his entry is given the Ottawa serial number 6242, in row seventeen about two-thirds down the page.

The Register recorded various details about each individual; name, port, place and date of registration; number and date of issue of any certificates received; amount of head tax paid; sex; age; city or village, district, province of birth in China and last place of domicile; occupation; and the port and date of arrival and name of vessel on which the immigrant arrived.

LAM Ching Ling or JUNG Ah Tuen as he was then called, was listed as a “Canneryboy” and it’s notable that his height of five feet one inch was recorded and various facial markings such as moles and scars were listed under column nineteen, Physical Marks or Peculiarities. The Canadian government went to great lengths to identify and keep track of all these immigrant to the country.

General Register of Chinese Immigration page for LAM Ching Ling, serial no. 6242, http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=immfrochi&id=6242&lang=eng

During his lifetime in Canada, LAM Ching Ling was known by various names. These included JUNG Ah Tuan, JUNG Ah Leun, LAM Ling, LEM Ling, CHUNG Chong, LIM Chong Ling, Hong Woo LAM and Hong Wo LAM. He is listed as LAM Duck Hew on some documents issued to his children.

He was commonly referred to as LAM Ching Lam, which may be spelled in Jyutping as LAM4 Zoeing1 Ling6. (The numbers refer to the Cantonese language tones.) The Chinese characters for this name are shown on his Chinese Immigration C.I.9 travel certificate issued in 1927, and are read from left to right.

C.I.9 travel permit issued to JUNG Ah Luen in 1927 https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_t16601/382

On his grave marker at Mountain View Cemetery in Vancouver, his name written in Chinese characters can be spelled in Jyutping as LAM4 Dak1 Diu6. This may be his name taken after marriage. LAM is the first character of the column, Dak Diu are the third and fourth. The second character, Gong, is an honorific used to respectfully refer to the deceased male.

ZIU6, Zhao, Chew, Chiu, Chu, Jew

CHEW Gore was born on 9 April 1875, in Sun Wui (Sun Woy, Xinhui) county, Kwangtung (Guangdong) province, China. Some documents list her birth village as Sue Kai; others list it as Kwo Jung, the same village where her husband was born.

Photograph from LAM Chew See’s C.I.44 document issued in 1924. https://recherche-collection-search.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/home/record?idnumber=254727&app=immfrochi&ecopy=t-16183-00109

She departed from Hong Kong aboard the vessel Empress of Japan and arrived at Vancouver in June 1899. She was registered under her birth name JEW Gow.

General Register of Chinese Immigration page for JEW Gow, serial no. 30707. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=immfrochi&id=30712&lang=eng

She had travelled to Canada with her husband, LAM Ching Ling, recorded this time in the General Register as LEM Ling, and their seven months old daughter, LEM Kim Fon. LAM Ching Ling had returned to China sometime in the late 1890s.

He was now classified as a merchant and head tax payments for himself and daughter LEM Kim Gon were later refunded. It would be expected that JEW Gow, being a merchant’s wife, would have been exempted from the head tax payment as well, but she was classified as a housewife upon entry and pays the $50 fee.

After marriage JEW Gow would often be referred to as LAM Chew Shee, meaning “a woman born of the CHEW clan and married to a LAM”.

LAM Ching Ling and LAM Chew Shee had six children:

The eldest child and first daughter was Kim Fon, also known as Fanny. She was born in 1898, in China. She died in 1918.

The next five children were all born in Canada. Names are shown in English, Jyutping, and Pinyin romanization.

Mary (LAM4 Ping4 Ngoi3, LIN Pingxi) born, 31 October 1900, died 1990;

George (LAM4 Fuk1 Tin4, LIN Futian) born, 20 March 1904, died 1970;

John (LAM4 Fuk1 Coeng4, LIN Fuxiang) born in 1908, died 1922;

Jessie born on 24 October 1910, died in 1995; and

Dorathea (LAM4 Cai4 Mei5, LIN Qimei, ) born on 9 September 1916, died in 1947.

Mary LAM was born in Steveston. A doctor was present at her birth. LAM Duck Heu is named as her father and it is recorded that she is the second child born to CHEW Shee. Their address is given as 1452 East 11th Avenue in Vancouver.

Birth Registration certificate for Mary LAM. https://search-collections.royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/Image/Genealogy/f722893d-be21-43ab-bfc8-3248a82fad44

An entry for the LAM Ching Ling family has been recorded in each Census of Canada for the years 1901, 1911, 1921, and 1931. (The microfilm records of these documents are often of poor quality, making the deciphering of the census taker’s handwriting difficult. Sometimes the handwriting itself is almost illegible. The names given are taken from the Ancestry.ca website, and often represent their researcher’s “best guess”.)

In the 1901 Census of Canada, LAM Ching Ling is listed as LING Lim, 28, living and working in Richmond, B.C. as a General Merchant. Named, as well, are his wife, Gem Ling, 26, and two daughters: Com Fung Lung, 2, and Ping Wye Ling, 1., lines 39-42. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=census&id=33558608&lang=eng

In the 1911 Census of Canada, he is listed as HONGWO, Isac, 37, and residing at 9 Broadway E. in Vancouver. His family includes wife Laren, 35, and five children: daughters Mung, 12, Mary, 10, and Bessie, 8 months; and sons George, 7, and Charot, 2., lines 22-28. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=census&id=6818361&lang=eng

Entry for the LAM Family in the 1911 Census of Canada.

In the 1921 Census of Canada, he is listed LING Lenn, 48, and residing at 605 Broadway E. in Vancouver. His spouse is Chee Ling, 46, and their five children are George, 17, John 13, Mary, 20, Jessie, 10, and Dora, 5., lines 44-50. http://central.baclac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=census&id=66466013&lang=eng

In the 1931 Census of Canada, he is listed as LAM Hongwo, 57, and living at 1452 East 11th Avenue in Vancouver. He is classified as a merchant working in a general store. Family members include wife Stell, 55, and four children: Mary, 28, Jessie, 20, George, 26, and Dora, 15., lines 42-47. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=census&id=85837223&lang=eng

On 28 June 1924, in Vancouver, LAM Ching Ling, and his family, registered as per Section 18 of the Chinese Immigration (Exclusion) Act of 1923. Every person of Chinese descent or origin (i.e. immigrant or native-born) was required to register his or her presence with a government official. These were often local police officers or postmasters. LAM Ching Ling was issued C.I.44 certificate number 52656. Note that he is referred to as CHUNG Chong.

http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=immfrochi&id=254954&lang=eng

On this document, his family is listed as: wife LIM Chew Shee, 1 son LIM Fook Ten (George), 3 daughters LIM Ping Oy (Mary), LIM Chu Yen (Jessie), and LIM Tie Mee (Dora). Daughter Fanny (Kim Fon) had passed away in 1918, and second son John in 1922.

http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=immfrochi&id=254727&lang=eng

http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=immfrochi&id=254662&lang=eng

http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=immfrochi&id=254664&lang=eng

http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=immfrochi&id=254658&lang=eng

http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=immfrochi&id=254660&lang=eng

The Canadian government implemented an expansive system of paperwork to record, track, monitor and control the movements of the Chinese people travelling to, from and within Canada. Upon arrival and after registration, a new immigrant would receive their head tax certificate, known as the C.I.5 or C.I.30 if exempted from payment, which served as the primary means of identification. If lost or destroyed, a C.I.28 was issued as a replacement.

JEW Gow’s C.I.5 certificate is replaced by C.I.28 certificate no. 12219, on 1 December 1924, although it had been endorsed as early as 28 June 1924.

Page from the C.I.28 Register for JEW Gow, no. 12219. https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_t3486/710

On 13 June 1925, LAM Ching Ling’s C.I.5 certificate, is either lost or damaged, and is replaced by C.I.28 certificate no. 12350.

Page from the C.I. 28 Register for LAM Ching Ling, no. 12350. https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_t3486/711

During this time, any Chinese person wishing to leave Canada temporarily had to apply for a special travel document known as a C.I.9 certificate. On 7 July 1927, the LAM family received theirs for an intended trip to Seattle, Washington by CPR Local rail. On LAM Ching Ling’s C.I.9 no. 59670, his proper name is given as JUNG Ah Luen. https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_t16601/382

Note the lack of a signature on CHEW Gore’s document. https://heritage.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.lac_reel_t16601/383

In the 1931 Census of Canada, LAM Ching Ling and his family are listed at 1452 East 11th Avenue, District 235 Vancouver Burrard, sub-district no. 52, Vancouver City, p.9. He is named as LAM Hongwo. Occupations are listed for each family member: LAM Hong Wo – merchant; his wife Shee – homemaker; Mary – teacher; Jessie – stenographer; George – laborer; and Dora – student.

LAM Ching Lam died on 20 August 1939. His obituary appeared in the Vancouver Daily Province, 21 August 1939. page 13.

The funeral procession was noted in the Vancouver Sun, 24 August 1939, page 12.

Services for LAM Ching Ling were described in the Vancouver Daily Province, 24 August 1939, page 24. Note the mention of a brother living in Steveston.

LAM Ching Ling is interred at Mountain View Cemetery in Vancouver and is recorded as CHUNG Ling Lam in its database. https://covapp.vancouver.ca/BurialIndex/PersonDetail.aspx?PersonId=d1c14bed-1f6c-420e-a290-2c63fbdcbc7e

LAM Chew Shee died on 20 February 1947. Place of burial is Mountain View Cemetery, Vancouver, B.C. Her obituary appeared in the Vancouver Daily Province, 22 February 1947.

Most members of the LAM family are interred or commemorated at Mountain View Cemetery, in Vancouver, B.C. Photographs were taken on 22 March 2025.

Translation of the Chinese characters is approximately as follows.

On the left side, four characters: Woman of the CHEW clan who entered the LAM household.

On the left side column: The grave of Mrs. LAM Dak Diu.

On the right side column: The grave of Mr. LAM Dak Diu

Frank Shong is the husband of Mary Mah.

Conclusion

The City of Richmond Archives has a significant number of records from the Hong Wo Store. These records, currently being cleaned by a conservator, will be accessible to researchers, possibly by the end of 2025. A preliminary review of some of these documents, as well as others, leads me to believe that LAM Ching Ling’s brother was involved in the store’s operation. That idea, the achievements of some of the children of LAM Ching Ling and CHEW Gore, and the stories of Richmond’s other pioneer Chinese Canadian families, will all be the subjects of posts in the future.

You must be logged in to post a comment.