Anyone who has lived along the water in areas where the fishing industry operates is familiar with fish net floats. Picked up on beaches while beachcombing, strung on ropes to make ornamental fencing or to decorate the verandas of beach cabins, floats are an instantly recognizable symbol of life on the beach.

Plastic floats have taken over the market since the 1950s, but before then fishing floats were almost exclusively made of cork or wood. The wooden ones were known as “cedar corks” and the only commercial supplier of them on the West Coast was Thomas Goulding who produced them in his Cork Mill at the Acme Cannery on Sea Island.

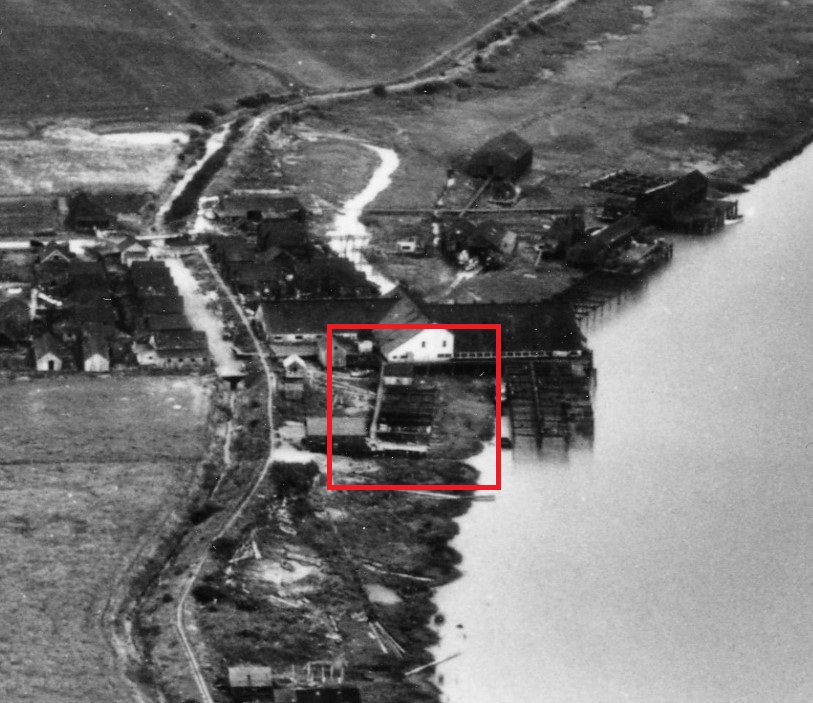

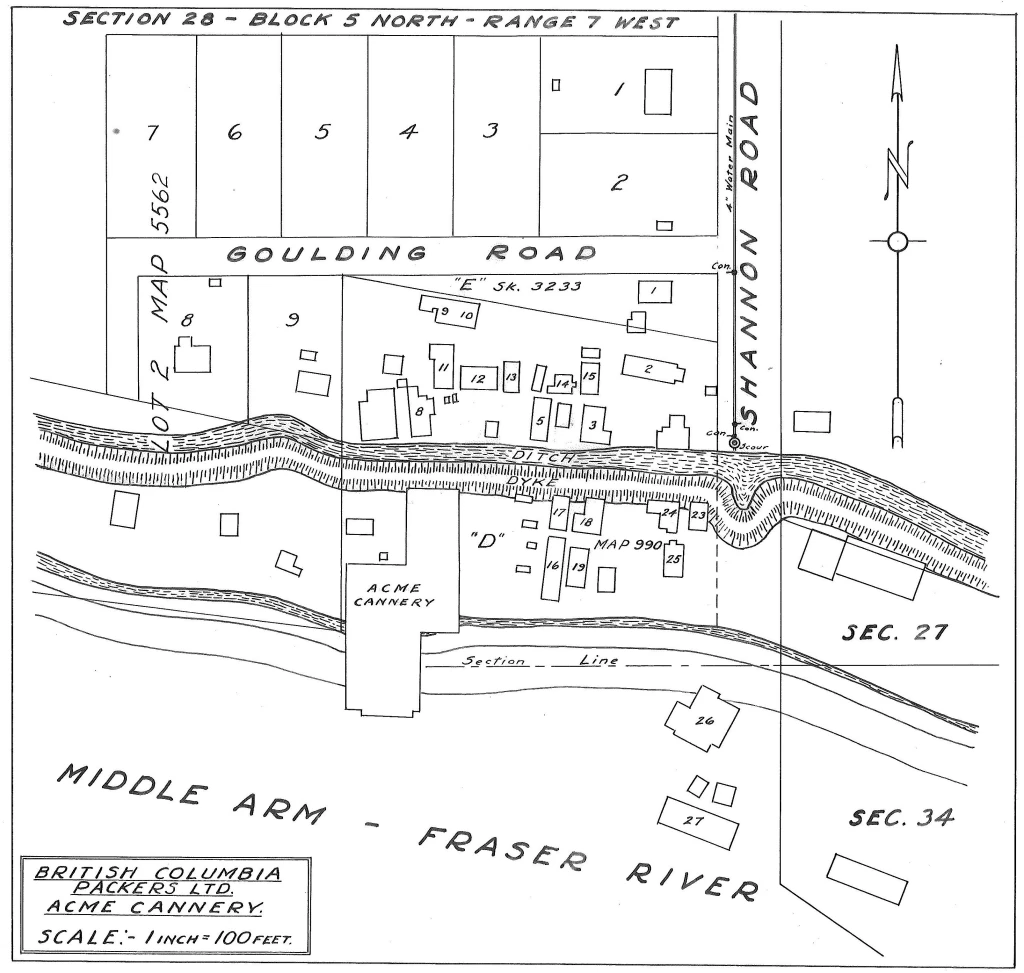

The Acme Cannery was built in 1899, part of the boom in cannery construction during the late 19th and early 20th centuries to take advantage of the seemingly unlimited supply of salmon available in the Fraser River. In 1902 it was absorbed into the British Columbia Packers amalgamation. In 1918 it closed, but the buildings, net racks and moorage were maintained for the community of fishermen, mostly Japanese, who lived around it. In a small building on the west side of the cannery Mr. Goulding set up the cork mill. The building and all the equipment for the mill, the saws, the lathes, the reamer, the stringer and the tar vat were all hand-built by him with help from his Japanese neighbours.

Work at the Cork Mill was seasonal. It sat idle during the fishing and canning season, operating only during the winter and spring. Western red cedar logs were supplied by coastal fishermen, found floating free or onshore in the Gulf of Georgia or possibly “liberated” from booms. The logs were cut into “cork bolts,” about four inches by four inches by four feet long.

Making the corks was fairly straightforward. The cork bolts were cut into blocks of either six or eight inches. A hole was bored through the centre of the cork which was smoothed and chamfered to prevent damaging the fishing net’s rope. The corks were then turned into their oval shapes on the mill’s lathes. A good day’s work could produce 2000 corks, ready for the next step in their production.

Tom Goulding’s granddaughter, Doreen Montgomery Braverman, worked at her grandfather’s cork mill occasionally after school and described her part in the process. “The next step was to thread them onto twine in lots of ten. That was the job they sometimes let me do. A reef knot tied the twine together so the floats could be dipped into a vat of hot tar to preserve them. They dried on net racks next to the vat.”

Completed cedar corks were likely shipped out by boat, there being no road access to the mill. Distribution of the product was carried out by the various fishing companies, BC Packers, Nelson Brothers, J.H. Todd, Canadian Fishing Company, etc. The users of the corks were gillnet fishermen who would attach the floats to their nets using a crochet stitch. This was another job which could be done by young people, earning $15 per net, a job that could take several days.

Running the mill required a number of workers. Fishermen, both Japanese and European, found and delivered cork bolts. The mill itself had a core group of workers. Gordy Bicknell was second in command at the mill. Alice Gillespie, Francie Edwards, family members, neighbours and friends rounded out the workforce. When the Japanese families were forcibly removed from the West Coast in 1942, the loss of the work provided by those neighbours caused difficulty in supplying cork bolts for the mill, but work continued.

By the 1950s the use of plastic foam corks was cutting into demand for the ones produced at the mill. Around 1954 an expansion of the Vancouver Airport resulted in a runway extension into south-west Sea Island signaling the doom of the small community and industries there. The land was expropriated by Crown Assets, houses were torn down or moved and the canneries were razed, along with the cork mill. The only evidence of their existence that remains are old pilings that once supported the canneries.

See also https://richmondarchives.ca/2015/01/06/japanese-canadians-on-sea-island/

Pingback: Keeping an Industry Afloat – Thomas Goulding’s Cork Mill – fisherynation.com